Holl sent = All Saints’ day. I walk to the library through the forest and find myself contemplating and puzzling over shadows of images from a childhood in Brittany. Perhaps because a raven is making knocking sounds, xylophone like. The Pacific ocean is reassuringly to the West, as was the Atlantic way back. Fall has come, winter is near, and children last night reminded me of a world of spirits and bogeys that are invited to come out on the night of October 31. To set the mood, Shostakovitch’s piano trio No. 2 in E minor, op. 67, will do. There was no Halloween in the Tregor of my youth, just stories told about ghosts in many a winter’s evenings. Stories of young men going around a countryside of isolated farms in the middle of the night to scare sleeping families. They put lit candles in carved out beets and turnips and hoisted them on a pole long enough to be waved across windows, even second floor windows if farmers were rich and deserved to be frightened by vengeful spirits. Or so we were told, round and round.

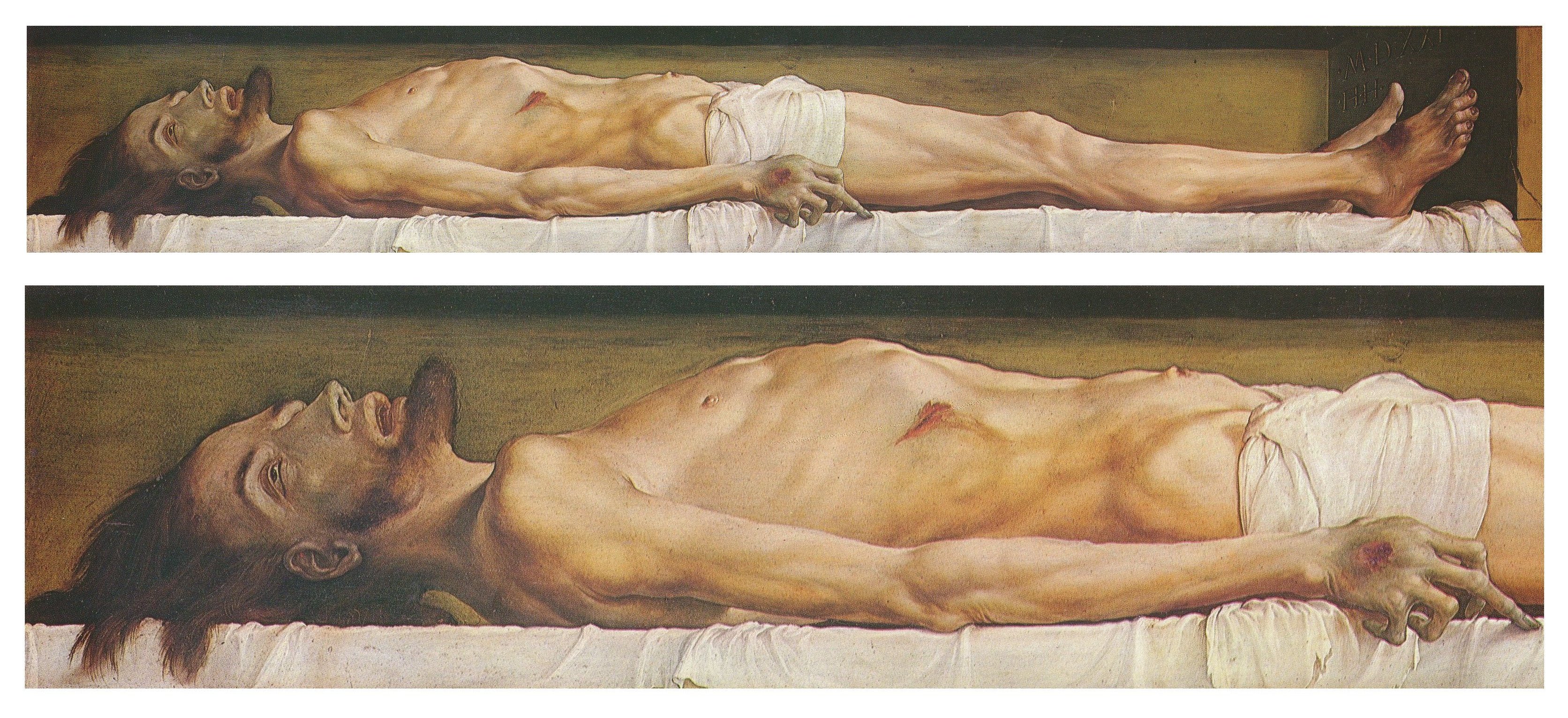

Largo movement of the Shostakovitch. On the first day of November, the village celebrated All Saints’ day, Gouel an Holl Sent. It was followed by the Day of the Dead, “jour des morts” in French or “deiz an Anaon” in Breton, day of the souls. This was part of a tangled history, a long-in-coming victory by the Church, since the early sixteenth century or so, when the idea that the dead were not really dead and one could live with them, even cajole, threaten, and use them, was put to rest. Nearly. Christianity was about the dead being really dead. A Mantegna already showed so (below: The Dead Christ). And soon after Mantegna, Holbein and his portrait of the deposition of Christ (below). We were to be birthed on the day of our death. Our saint’s day—which was the date of their death—was what counted, not the day of birth of our biological machine. Life was a long parturition. A project.

And yet. To prepare for these two days, in the cemetery surrounding the village church and not yet replaced by a parking lot and commercial mall, graves were straightened, weeded, cleaned, no matter the weather at this time of the year. We helped plant daisies and bring large bouquets of chrysanthemons or peonies. Unattended tombs could be cleaned and flowered by a neighbor who remembered the family. With her bucket and brush, kneeling on the creaking gravel, an aunt brushed and washed her family’s tomb with such intensity her knuckles bled. We couldn’t tell if hair was disheveled and cheeks wet because of wind and rain. One day, a saints’ day or other, one of the great tides or our forgiving ocean would swallow and wash away all of these bloodied and pained souls. Graves would list, and we would forget how to sing In paradisum deducant te angeli.