On January 18, 2021, I listened to MLK’s last speech and was again moved by his radical call to justice, his courage to go beyond the timorous personal interests, safety and longevity. “The right to defend rights… I’ve been to the mountain top… I’ve seen the promised land… I’ve seen the glory…”

This dramatic ritual makes me think about the notion of duty to remember, right before Yom ha-Shoa, which begins in Israel on the evening of the 7th of April. On the expression in French, current since the nineties, of le devoir de mémoire, I quote François Dosse:

L’historien a ici pour tâche de traduire, de nommer ce qui n’est plus, ce qui fut autre, en des termes contemporains. Il se heurte là à une impossible adéquation parfaite entre sa langue et son objet et cela le contraint à un effort d’imagination pour assurer le transfert nécessaire dans un autre présent que le sien et faire en sorte qu’il soit lisible par ses contemporains (F. Dosse, “Le moment Ricœur de l’opération historiographique”, in Vingtième siècle 69 (2001): 139)

In English:

The historians’ task here is to translate, to name what is no longer, what was other, in contemporary terms. In doing so, they come up against the impossibility of a perfect match between their language(s) and their object(s). This forces them to use their imagination to ensure the necessary transfer to a present other than their own and ensure that it is readable by their contemporaries.

The first use of the expression, according to the records of the Institut National de l’Audiovisuel (INA), which archives French radio and television programs, dates to 1988 (radio) and 1992 (TV). It happened relatively late, in spite of the existence of archival notices that refer to early testimonies of the forties to the seventies as using this expression. These notices may have been written under the influence of another “present,” however, that of the eighties and nineties.

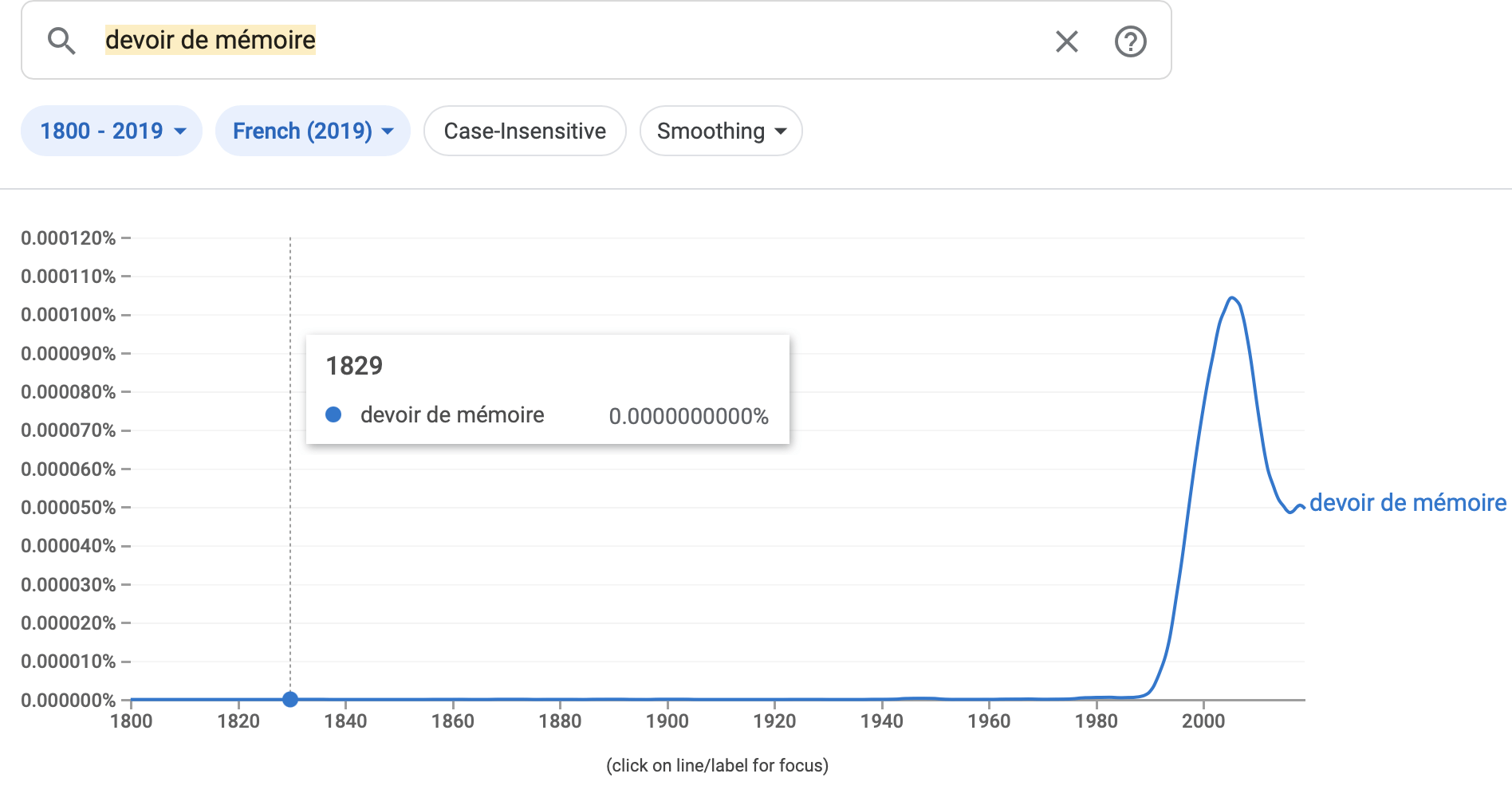

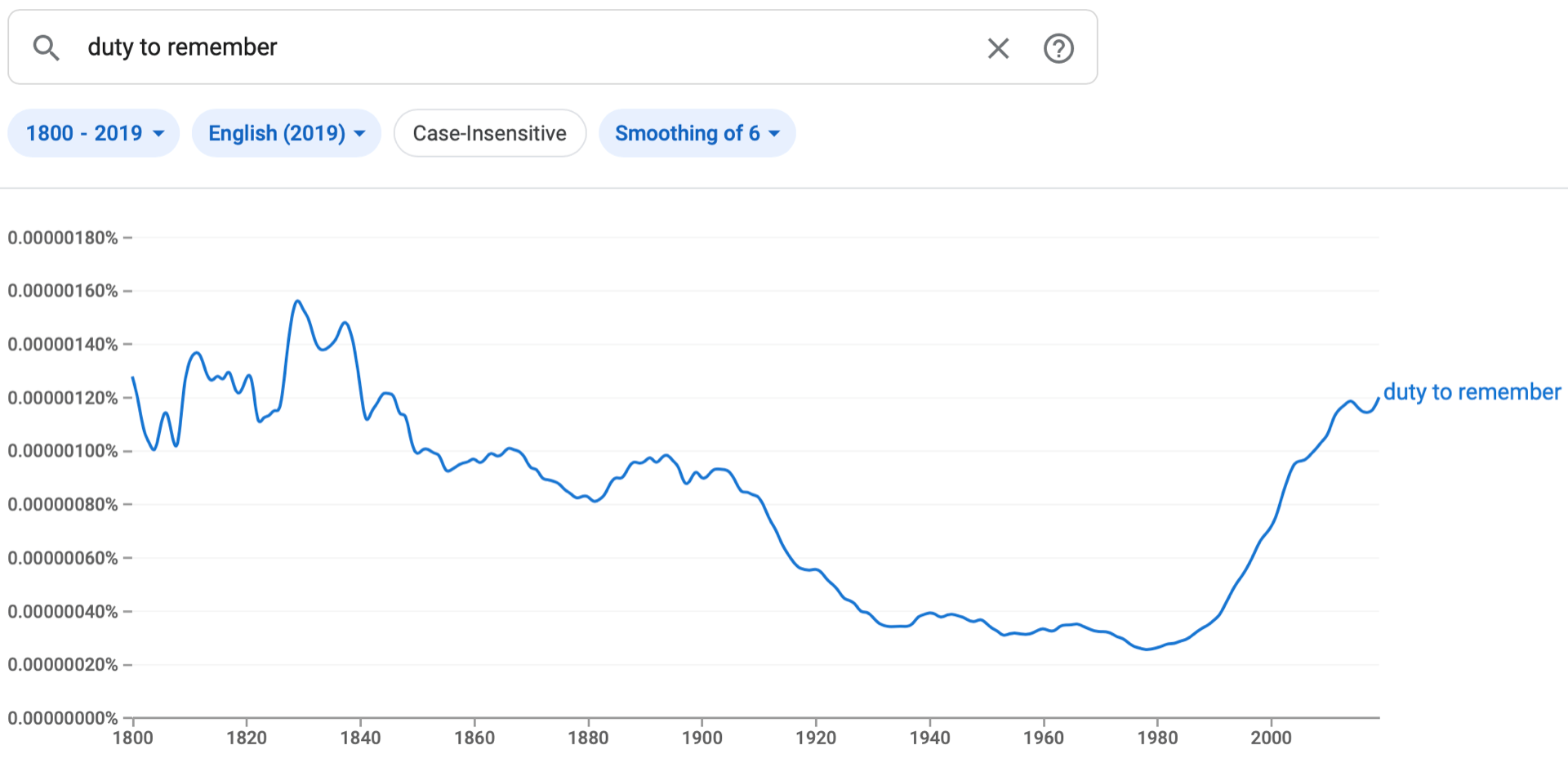

If one looks at different media more widely, one sees that the expression “devoir de mémoire” takes off in the 1990s in French books. The Google Ngram viewer (books) confirms that the y-curb takes off for French from 1990 on. The English equivalent, the “duty to remember” (see the second diagram below), has a more complicated history, it seems, but I won’t go into it here. The ngram curve for “duty to remember” is at its lowest in 1980 and picks up consistently in 1990 and on, in parallel with the curve for “le devoir de mémoire.”

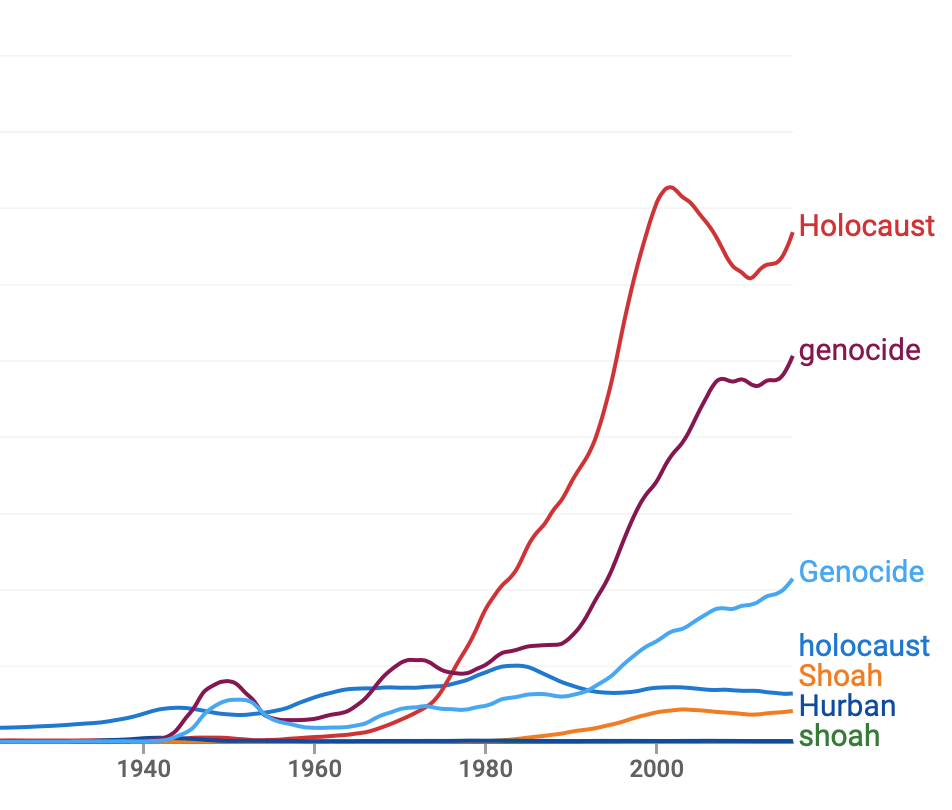

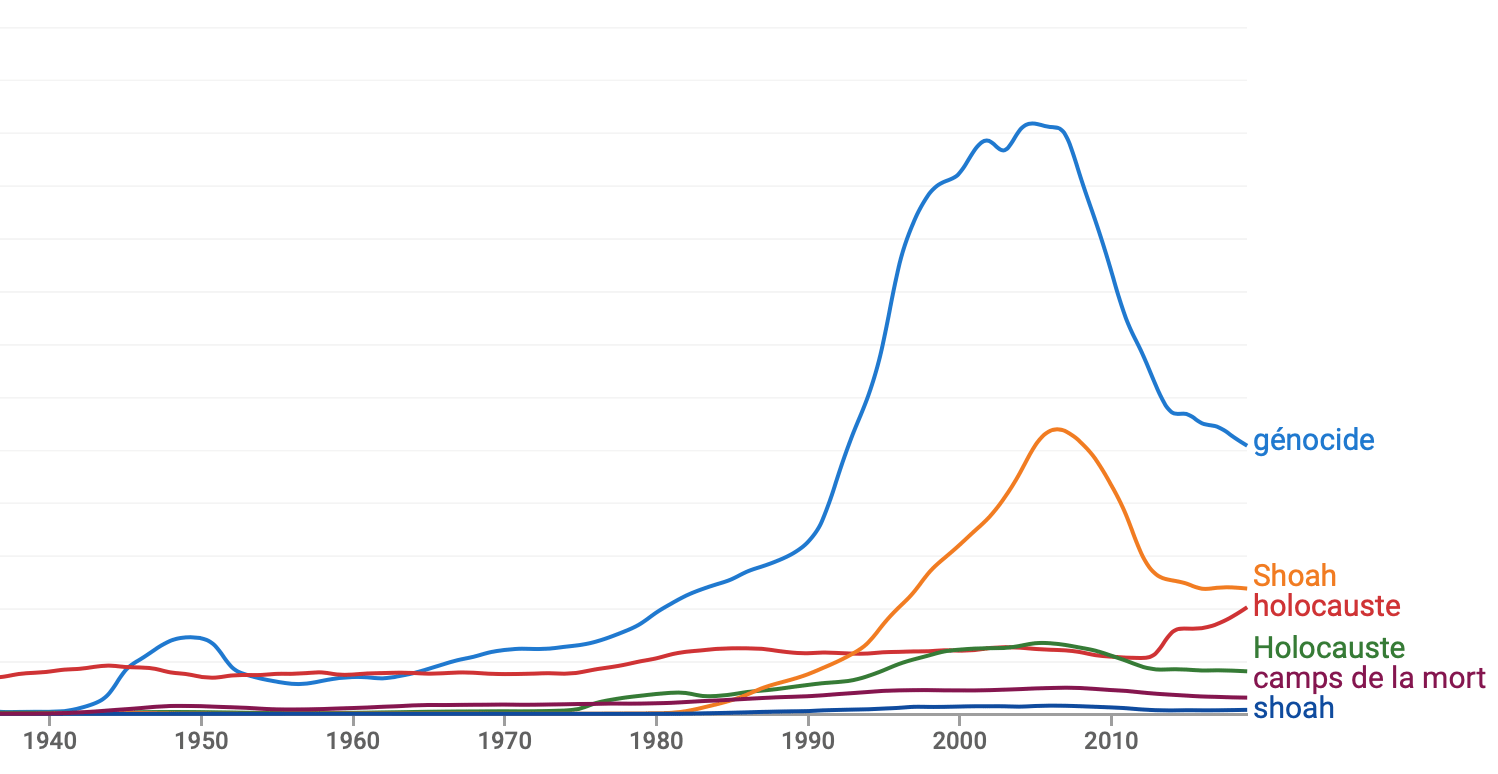

This datable irruption of a devoir de mémoire got me interested in the fate of the word holocauste in French culture. The word has long been used in ancient Greek and Christian (Catholic) liturgy. It meant an offering that was entirely devoted to a divinity and burned, for instance in an animal sacrifice. In its more recent use in French for the murder of Jews in WW II, two main steps seem to have been significant. One phase would be its restricted use for many years—since the fifties—by the author of La nuit, Elie Wiesel, because of its evocation of fire and the story of the ’aqedah, but unfortunately joined to François Mauriac’s Christological interpretation. Wiesel abandoned the use of that word because he felt that it had become used all too superficially. This may have happened in the late seventies, in reaction to the US film mini-series The Holocaust and the ensuing commodification of the word. The second step in the increased use of the word holocauste starts already with Eichmann’s trial in 1961 and continues with the influence of The Holocaust US series (1978), itself a competitor of Roots. The capitalized form—the Holocaust—takes off in the seventies, while the non-capitalized word has always been in usage, most probably because of its liturgical and biblical importance. Its renewed usage in French in the seventies, with a new meaning, corresponds to the massive decline of Christian practice, especially Sunday mass, its readings and prayers. In English, the word “holocaust” evolved much earlier into a metaphor and made a secular meaning possible. Its religious charge became diffuse in the seventeenth and eighteenth century according to the Oxford English Dictionary, and the word could apply to a local fire or catastrophe, often with a considerable number of victims.

Shoah, in its US spelling (it is also spelled Shoa and Sho’ah), has been spreading in French since the early eighties, especially since Claude Lanzmann’s film of the same title (1985). It competes with French holocauste or English holocaust, but has remained limited in usage. Much more limited yet, at least outside of Jewish religious circles, is Hebrew/Yiddish churban or khurbn eyrope. It has the tangled advantage of situating the event in a long historical chain bound to the destruction of the two temples but is linguistically and theologically baffling for non-Jews and even for many Jews. One wonders what Elie Wiesel, quoted above, made of this element from his mama loshen. Holocauste has seen a decline in French but is as current in English as genocide. See those terms in the Google Ngram viewer for further evidence of these reconstructions of the past with feelings and notions of the present.

Back briefly to the contemporeanousness of multiple presents and pasts that historians are expected to navigate expertly. Or rather back to their porosity. The borders between the assumed present memories are not clear. Neither are those between past(s) and present(s). Something real, however, points beyond “holocaust” and “genocide,” the markers of a live, present, evolving collective memory. The present memorialization is partly created of new cloth (“genocide” is a neologism) and partly made out of the débris of an ancient “memory palace” (“holocaust”). What does it mean for us to remember and reconstruct a past on the basis of a re-imagined present whose social structures seem so difficult to grasp? Or: Doesn’t the call to remember need the support of historical inquiry, and vice-versa? This question is triggered by my reading of Maurice Halbwachs’ Les cadres sociaux de la mémoire (Paris: Colin, 1925), especially the last two chapters on religious and social memory. An English version exists: On Collective Memory (Chicago: 1992).